The Innovator′s Way – Essential Practices for Successful Innovation: Essential Practices for Successful Innovation

CHAPTER 1 Invention is Not Enough

Peter J. Denning

Robert Dunham

DRAFT v22 — 9/5/09

Innovation is not simply invention; it is inventiveness put to use.

Invention without innovation is a pastime.

–Harold Evans

Every revolutionary idea seems to evoke three stages of reaction:

It’s completely impossible. It’s possible, but it’s not worth doing.

I said it was a good idea all along.

Arthur C. Clark

Innovation is one of the most vexing challenges of our time. According to Business Week in August 2005, our overall success rate with innovation initiatives is an abysmal 4%. Many people have grown impatient with the staggering waste of energy and resources invested with such a poor return. We cannot hide from this problem because innovation is essential for personal, business, and economic success.

Our collective effort to meet this challenge has been prodigious. In September 2009, Amazon.com reported 9,300 printed books with innovation in their titles. Yet all our effort and ingenuity has not lifted us to a success rate better than 4%. What are we missing?

Those books tend to look in just four categories for answers — talent, creativity, process, and leadership. These categories have yielded few useful new answers. They have not escaped the box, merely repackaged it with new paper and a fresh ribbon.

In puzzling over the nature of the box, we noticed two exceptions to the 4% success pattern. One is “serial innovators”, who produce one innovation after another, often with success rates over 50%. The other is “collaboration networks”, volunteer groups with little management and light leadership; the Internet, World Wide Web, and Linux operating system are examples. In both cases, personal skill seems to play an essential role.

Here, in this book, we explore a new category — personal skills — and we find promising new answers. Our fundamental claim is that by developing their skills in eight practices, individuals and groups can become competent innovators with success rates much higher than 4%. We identified the eight practices after extensively studying the actions of many innovators.

The eight practices are essential. They are not discretionary techniques. If you want to succeed, you need to succeed with every one of them. If any one of them fails to produce its intended outcome, the innovation will fail.

The eight practices are conversational. Their characteristic structures and failure modes are easily accessible for learning. Everything we recommend for learning is observable, measurable, and doable. Our framework offers a new way of observing both innovation practice and the consequences of innovator actions on the willingness of people to adopt.

However, success depends on more than knowing what the conversations are, it depends on your skill at executing them. Your embodied skills — your automatic habits — matter more than your ability to follow a checklist. The reality of life does not allow any other way. The pace of events in most conversations involving a network of people is too fast for your mind to think things through; your automatic reactions have to be the right ones. Your embodiment of the practices is essential to allow you to react effectively and smoothly in real time.

We realize that the claim that innovation is a skill is outside the current common sense about innovation. The notion of personal skills for innovation may sound fuzzy and nebulous. In this book, we will remove the fuzziness: With the help of language-action philosophy, we offer a rigorous treatment of the skills and show a reliable path to success with them.

The Hero, The Lucky Stiff, and The Generator

Where does success at innovation come from? When Louis Pasteur invented the anthrax vaccine, Bill Gates the Microsoft Corporation, or Tim Berners-Lee the World Wide Web, did their success come from natural talent, hard work, and determination? Or were they just lucky, happening to be in the right places at the right times? Would someone else have done these things when the times were ripe?

The standard stories about the people behind successful innovation are mainly of two kinds. The hero innovator is the naturally gifted individual (or organization) who brings about the innovation through talent, grit, determination, and single-minded devotion to the goal. The luck stiff innovator is the individual (or organization) who happened to be in the right place at the right time, and had the good sense to seize the moment.

Malcolm Gladwell (2008) artfully analyzes the histories of well-known innovators such as Bill Gates and Bill Joy and finds that their stories can be told either way. They are simultaneously heroes and lucky stiffs. He adds that part of their good fortunate was to be raised by families that valued finding and reaching out for new possibilities. However, neither form of story offers much guidance on what others can do to achieve similar successes.

This book is about a third kind of innovator, the generator (short for generative innovator). A generator is an individual (or organization) who senses and moves into opportunities to take care of people’s concerns, and mobilizes people to adopt a new practice for taking care of their concerns. Geoff Golvin (2008) argues convincingly that many “heroes” are actually generators who got that way through sustained and deliberate practice.

This is a story of hope because, as we shall see, innovation generators all engage in the same eight essential practices, no matter what their field. We will illustrate in Chapter 2 with the stories of six innovators, showing exactly how they went about generating their innovations. It is true that they worked hard and that they were presented with unexpected, fortunate opportunities. But their success was not dependent on raw talent or pure luck, it was the product of skills that they learned.

The good news is that you can learn them too.

Rethinking How we Define Innovation

The first step in preparing to become a generator is to have a clear and rigorous definition of the outcome of innovation.

The variety of working definitions of innovation makes this a real challenge. The typical definitions say innovation is inventing something novel, introducing new ideas, making changes, or bucking traditions. So is innovation the invention, the idea, the change, or the struggle? If we pose the question that way, we are in for a lively debate but no real agreement.

If we pose a slightly different question, “When does an innovation succeed?” we can get to a clear, uncontroversial definition. Innovation succeeds when an idea is put into practice. The process of accomplishing this is likely to include inventions, ideas, changes, and struggles … but there is no innovation until a community of people adopts a new practice. Adoption is the key to success. That leads to the definition on which this book is based:

| Innovation is adoption of new practice in a community. |

This definition is at the intersection of the notions of inventing, introducing ideas, making changes, and bucking traditions. It is rigorous and sets a strong criterion for innovation. If you want innovation to succeed, you focus on adoption.

This definition makes a sharp distinction between innovation and invention. Invention is the creation of new ideas, artifacts, processes, or methods. Inventions become innovations only when they are adopted into practice. Innovation does not cause adoption; it is adoption.

This is not a new insight; Peter Drucker (1985) made it forcefully years ago. The difficulty is that many people do not bring this distinction into their practice. Because they believe that invention is the key source of innovation, they channel considerable effort and resources into creation of new ideas. Many also believe that innovation is more likely to result when they are organized around the right process, and they channel their resources and energy into process definition and management. While it is true that invention and process are important, they are not enough to bring about adoptions. In the next three sections, we will say why these beliefs are insufficient for innovation.

Invention Is Not Enough

There is a common, deeply held, and revered belief that inventions are the main cause of innovations. We call this belief the Invention Myth.

Those who hold this belief seek innovation by looking for ways to stimulate creativity. This is done by exercises in everything from conceptual blockbusting to design of workplaces that enhance conceptual stimulation. They believe that if they are not cooking up ideas, they cannot innovate. They must constantly stir things up to keep the ideas flowing. They believe that this is the only way to overcome the high failure rate of innovation initiatives.

This belief pervades many government policies. Major reports call for more government spending on university research and for tax incentives for companies to do research.

There is an attractive and compelling logic behind this belief. If you look backwards in time from when an innovation is in place, you can usually locate the key idea on which it is based and the first person to propose the idea. That person becomes the hero of the story about how the idea changed the world. However, the person who first proposed the idea did not necessarily cause the chains of events leading to the adoption of the idea. Creating new ideas is fundamentally different from getting people to adopt them.

How strong is the evidence supporting the invention belief?

It is not all that strong. Peter Drucker (1985) reported that only about 1 in 500 patented inventions returns more than its investment; he believed that new knowledge is the least likely source of innovation. In a study for the National Research Council of the connection between basic research and innovation, Stephen Kline and Nathan Rosenberg (1986, p. 288) concluded, “the notion that innovation is initiated by research is wrong most of the time.” In his history of American innovation, Harold Evans (2004) analyzed 75 innovations and concluded that the innovators were almost always not the inventors.

Tim Berners-Lee (2000), who drove the development of the World Wide Web, spoke about how he changed his approach from inventor to innovator. He initially proposed a prototype browser and server on a NeXT computer. He was surprised at how little interest others showed in his invention. He quickly abandoned his “sell-the-invention” approach and moved instead to a “get-users-to-adopt” approach. He showed them how the browser readily obtained information of high value to them, especially calendars, research papers, and newsgroups. He discovered, in effect, that the invention myth would not take him to his goal.

Clearly, invention is important, but it is not enough to ensure success at adoption. An excessive emphasis on invention, rather than on adoption, is a major factor in the low success rate of innovation.

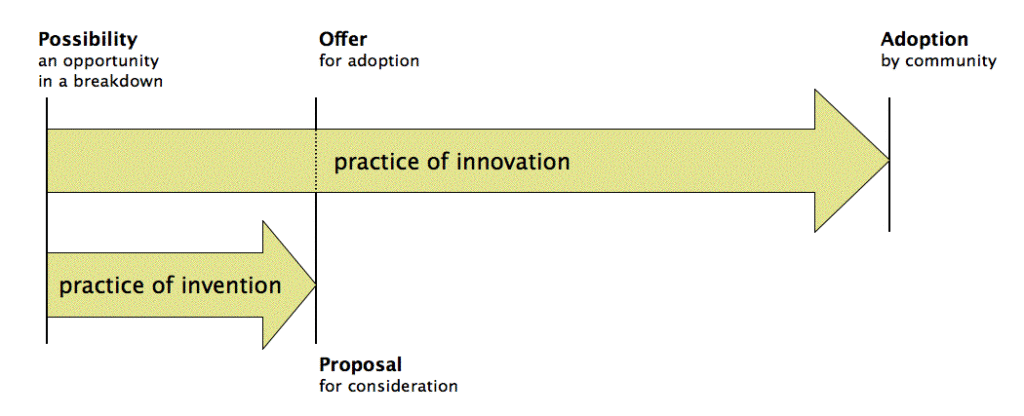

The diagram of Figure 1 compares invention and innovation as practices. The outcome of invention practice is an idea or prototype for consideration. The outcome of innovation practices is adoption of a new practice in a community.

Figure 1. Innovation and invention are related but different.

In a discussion of lessons for young innovators, Robert Metcalfe, the inventor of the Ethernet, compared invention to a flower and innovation to a weed (1999). He said that the Ethernet has a beautiful conceptual structure and elegant mathematical analysis of its operation. It is a wonderful flower. But the actual work of adoption is quite different. He said, “In my picture, it’s the dead of winter and I am in the dark in a Ramada Inn in Schenectady, New York. A telephone is ringing with my wakeup call at 6am, which is 3am in California, where I flew in from last night. Within the hour I’ll be in front of hostile strangers selling them on me, my company, and its strange products, which they have no idea they need. … If I persist, selling like this for 10 years, and I do it better and better each time, and I build a team to do everything else better and better each time, then I get my townhouse. Not because of my flowery flash of genius in some academic hothouse.”

Examples of Innovation

To drive these points home, we will illustrate the differences between invention and innovation with examples. The examples that follow show that these two notions can show up in at least five combinations. The final two examples — innovations without obvious inventors or innovators — have become common in the Internet.

1: Inventions that did not become innovations

8-Track Stereo Systems were invented in the US in the 1950s. They were endless-loop tape cartridges with four stereo sound tracks that could play continuous music for several hours before they repeated. US manufacturers pushed them hard beginning around 1965, but withdrew by 1975 when Japanese makers undercut them. The US consumer market moved on to cheaper, single-play tape cartridges in the 1980s and the Japanese followed suit. This invention could not be sustained as an innovation. Sony’s Betamax video tape system met a similar fate, losing to VHS in the 1970s. Toshiba and NEC HD-DVD system likewise lost out to the Blu-Ray system in 2008.

The Betamax system for formatting video tapes was introduced by Sony in the late 1970s. Although it was offered on the market before VHS, VHS eventually won out and was universally adopted. There are many stories about why Beta lost to VHS, but the most believable one is simply that VHS was the first to offer a two-hour recording. That was more valuable to consumers than what many engineers thought was a technically superior, more error resistant format.

Perpetual motion machines are inventions for which no innovator is possible. The Patent Office routinely denies applications for patents on machines that supposedly can run forever without new energy after they are started. That the laws of entropy guarantee that no such systems exist does not dampen the hopes of some inventors. The apparent discovery of cold fusion in 1990 rekindled a related hope for a process that could generate unlimited amounts of cheap energy. It also went nowhere.

2: Innovations by the inventor

Bob Metcalfe was the inventor of Ethernet. For much of the 1970s, the token ring network was the preferred way to connect computers. In this configuration, the computers circulate a fixed number of packets in a constant stream among themselves in a loop; computers insert data into empty packets on the ring and other computers remove data from full packets addressed to them. This method was the favorite of university research labs during the 1970s and had the marketing muscle of IBM behind it. But the Ethernet protocol, invented in 1973 by Metcalfe at Xerox Palo Alto Research Laboratory eventually won out and became an international standard. Computers broadcast new packets on a shared coaxial cable nicknamed “the ether”; and they listened on the cable for packets addressed to them. The Ethernet was cheaper to manufacture and it scaled up to large sizes more readily. But the real reason it succeeded is that Metcalfe founded a company, 3Com, and spent the next decade selling Ethernets and working with international standards bodies to have them standardized. In a 1999 interview about his accomplishment, his young interlocutor exclaimed, “Wow, it was the invention of the Ethernet that enabled you to buy your house in Boston’s Back Bay!” Metcalfe shot back: “No, I was able to afford that house because I sold Ethernets for ten years!” (Metcalfe 1999)

Edwin Armstrong was the father of modern radio. Many people do not know his name. They think that radio was invented by Marconi, RCA, Westinghouse, or General Electric. Armstrong invented four of the fundamental circuits used in radio; these circuits are used in virtually every sender and receiver today. They were the regenerative receiver (1912), the superheterodyne circuit (1918), the superregenerative receiver (1922), and the complete FM system (1933). He filed many patents on these circuits and spent many years in courts defending his patents against the big companies who wanted to use his inventions without paying the royalties.

He worked with big companies including RCA, General Electric, and Westinghouse to establish means of production for his radios. His five-tube syperheterodyne radio became the standard used in nearly every home during the heyday of radio in the 1920s and well into the 1950s. In the 1930s, his friend David Sarnoff at RCA turned against him and vigorously opposed FM because it would undermine RCA’s AM broadcast empire. Armstrong battled in the FCC to get approval for an FM band, against RCA’s opposition; RCA wanted the same bands for TV. He finally won FCC approval and built his own FM broadcast station in Alpine, NJ. Starting in 1942 he broadcast crystal-clear, static-free music to a market of people who had purchased his FM receivers from General Electric. In the early 1950s, RCA and numerous other companies changed their minds about FM and started building FM equipment in violation of his patents. He filed 21 lawsuits. But his financial situation became so desperate that in a moment of great despondency on January 31, 1954, he committed suicide by walking off his 13th floor balcony in New York City. His widow pursued the suits in courts for the next fifteen years, ultimately winning them all and receiving millions of dollars in payments. By the 1960s, the FM system was regarded as the superior system; today almost all radio sets include FM; all microwave and space transmissions are FM. Armstrong did not witness the full impact of his innovation during his lifetime. There can be little doubt that he was not only a great inventor, but also a great innovator who spent enormous energy in bringing about the adoption of his systems.

Genghis Khan created the Mongol Empire beginning in 1206. In 25 years he created a vast empire reaching from China to Eastern Europe (Weatherford 2004). Kahn’s empire was larger than the Roman Empire, which took over 400 years to build. Khan innovated in every battle, constantly learning from past successes and failures. He invented many new weapons and tactics, putting them immediately to the test, and retaining only those that worked well. His enemies could not keep up with him or prevent his swift advances. He also innovated in organizing and administering government.

Abraham Lincoln, an accomplished orator, carefully crafted the 1863 Gettysburg Address to offer a new conception of the United States of America. Prior to the address, the word “states” was the key word: the US was regarded as a loose republic of independent states. After that time, the word “united” became the key word: the US was seen as a nation, “one arising from many.” (Wills 1992). Lincoln’s message was an invention, and its eventual adoption into the practice of government of the United States was an innovation.

3: Innovations by someone other than the inventor

Gary Kildall was the true father of the personal computer operating system (Evans 2004). In his PhD research at the University of Washington in the early 1970s, he worked with one of the best-designed operating systems of all time, the Burroughs B5500, becoming thoroughly familiar with advanced concepts such as multitasking and interactive computing. Shortly thereafter, while an instructor at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, he acquired one of the new Intel 4004 process control chips for his lab. He soon realized that the 4004 was a general-purpose computer and not just a special purpose chip. He designed an operating system that used a floppy disk as its memory and incorporated the advanced concepts he had learned about operating systems. This program was called CP/M, for “control program, microprocessor”. Intel contracted with him to develop CP/M and an associated portable programming language PL/M, for the 8008 and later the 8080 chips. He started Digital Research, Inc., in Pacific Grove, to market CP/M, which quickly became the operating system of choice in the nascent microcomputer market in the late 1970s.

In the early 1980s, IBM decided to start its own PC effort and visited the young Bill Gates of Microsoft for an operating system. Gates referred them to Kildall. Kildall was not willing to sign IBM’s nondisclosure agreements. Miffed, IBM went back to Gates and decided to use Gate’s DOS, a quick-and-dirty CP/M knock-off. Kildall was infuriated that Gates would try to copy his software without license, but Gates, flanked by a phalanx of IBM lawyers, forced Kildall to back off. It took Gates another ten years to get the quality of MS-DOS up to the original CP/M system. Many people speculate that if Kildall had been more accommodating toward IBM, he would have closed a deal with IBM and he not Gates would be the industry’s magnate. Kildall was clearly an inventor but not a dedicated businessman; his invention made it into a relatively small market, the first PC users. Gates was not an inventor, but he was an astute businessman; he provided an innovative business model that eventually propelled Microsoft to a 90% market share of all PC operating systems. Kildall was the inventor of PC operating systems, Gates the innovator.

4: Innovations without an obvious inventor

In 1954 Ray Kroc opened the first McDonald’s restaurant in San Bernardino, California. He built the chain to 100 restaurants by 1959, bought all the rights from Mac and Dick McDonald in 1961, and continued to expand the chain to its present size of about 30,000 restaurants. Kroc’s innovation was an assembly line process to prepare hamburgers, cheeseburgers, and French fries so that customers could have their tasty, fresh hot food within two minutes of placing their orders. He also focused on choice locations for the stores. Kroc innovated with food-preparation process. He thought he got the idea from the original McDonald’s store, but others credit him with inventing the process as well. Many others imitated his business model, making fast food restaurants a way of life.

In 1971 the first Starbucks coffee house opened in Seattle. In 1982 Howard Schultz joined as director of retail operations and began to formulate a new vision of a coffee house: offering the finest coffees from around the world, beginning with espresso and latte from Italy. He transformed coffee from its image of concentrated, vile, day-end tar to an upscale experience of the up-and-coming generation. Today there are over 6,000 Starbucks stores worldwide and the number is growing. Morning latte is now a way of life.

In 1981, the National Science Foundation sponsored a project proposed by Peter Denning, David Farber, Tony Hearn, and Larry Landweber to build a community network for Computer Science researchers. Throughout the 1970s, the ARPANET had been available only to Defense Department agencies and contractors; it had about 120 nodes in 1980. CSNET implemented a version the Internet protocols TCP/IP over GTE Telenet, the only public packet data network in the US at the time. It built Phonenet, an extensive dial-in email relay network that imitated ARPANET email. It built a directory server and gateways to move traffic in and out of ARPANET. It built a network coordination center, which was the first Internet Service Provider (ISP). It built a governance structure so that member universities and research laboratories could pay dues to sustain the network and determine what services to include. By 1985 it was fully self-sustaining and was a complete prototype of the modern Internet environment. Its 165 member organizations around the world brought upwards of 50,000 students and researchers into the Internet. In the late 1980s, CSNET alumni helped build NSFNET, which became the backbone of the modern Internet and superceded CSNET in 1995. CSNET did not invent new technology. It created a social structure for an Internet community that propagated into many subsequent Internet communities.

In this category, innovators typically claim that they got their ideas from someone else or that the ideas were simply “in the air”. CSNET illustrates both. The innovators put into place a process that got a significant market to adopt prior inventions into standard practice. The innovators also “appropriated” ideas that were common in the research domain into operations in their community.

5: Innovations without obvious innovators

Wikipedia was started in 2001 by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger as a project to build a free-content, open-edited, on-line encyclopedia. Its articles are written and edited by (anonymous) volunteers. Every article has many authors and many editors. The articles represent a distillation of knowledge from many people in the community. Sanger defined the ground rules for contributing and editing and provided the web site. Wikipedia represents a final step in the demise of the traditional, scholarly encyclopedia. For many years, Encyclopedia Britannica had the unchallenged brand name and highest reputation for quality and scholarliness. When Microsoft started bundling Encarta, a much cheaper (and lower quality) encyclopedia on a CD with its Windows operating system, families stopped purchasing Britannica and the company had to change its business. Wikipedia has major gaps, especially in technology areas where the younger contributors have no knowledge of early contributions. Wikipedia has been controversial because its policy of allowing anyone to anonymously edit anything has allowed flagrant abuses and undermines the trustworthiness of many entries. Still, most people find the quality good enough and the price unbeatable.

In the late 1990s, a new genre of website appeared, known as the web-log, or simply blog, which was basically an ongoing diary and commentary by its editor. A few editors (known now as bloggers) stood out because their exceptional skill drew many readers. These bloggers began to affect public opinion outside the normal news and journalistic media. They came into the public eye when politicians discovered that blogs could and did influence voters. Anonymous programmers developed software kits to help the less experienced set up their own blogs and to help readers keep track of new postings on their favorite blogs. Blogging was a new practice that arose spontaneously within the Internet, providing a new channel of expression. Leaders emerged, but they were more like surfers riding waves than ships generating waves.

Like the previous category, this one might seem odd because some form of leadership was needed to bring people into the new practice. This is true. The leadership jumped from one person to another as anonymous people stepped forward and added something to the mix. The leadership was there, but no one person could be identified as the overall leader. The Internet has been a rich spawning ground for such innovations because it allows people who care deeply about an issue to find one another, form a critical mass, and work together to produce a change around their issue. Sometimes the community was guided by the watchful eye of a low key, light touch leader (as Linus Torvald in Linux), and sometimes the leadership passed from one unnamed person to another (as in blogging). (Tuomi 2003)

Conclusions

There is often no clear connection between inventions and innovations. There is often no clear pattern of an “idea that changed the world” — in fact, the “idea” was often invented as an afterthought to explain the new practice. What is clear is that, in every case, an identifiable community adopted a new practice. Examples like these gave us our focus on looking for what leads to adoption.

Process Is Not Enough

There is also a common, deeply held, and revered belief that innovations are the results of processes that can be managed. We call this belief the Process Myth.

Those who hold this belief seek innovation by looking for the right process, organizing their workplaces to facilitate the process, and closely managing the process. They believe that if they are not following process, they will be derailed and their chances for successful innovation, already small to start with, will evaporate.

This belief pervades many business innovation books. They lay out processes, the types of resources required, the risks to be analyzed, and ways of evaluating return-on-investment for innovation proposals. Many processes, for example, assume that ideas have sources; the corresponding management guidelines systematize the search for sources.

There is an attractive and compelling logic behind this belief. If you look backwards in time from when an innovation is in place, you can usually identify a series of steps from the initial idea to the present state. The steps make logical sense and follow a logical order. However, what you select as the steps depends strongly on your beliefs about how innovation is produced. And the order may be an illusion: some steps do not necessarily produce the conditions needed for the next step.

How strong is the evidence supporting the process belief?

It is not all that strong. In Chapter 3, we will examine the main process models of innovation and find significant shortcomings in each one. It is very difficult to conclude that any one model captures everything about innovation process. Moreover, the models are not easy to reconcile. Which process appeals to you depends on you biases — for example, if you believe innovation is about movement of ideas into the marketplace, you will find the pipeline model attractive; and if you believe that innovation is about people making decisions to adopt, you will find the diffusion model attractive.

The combination of the invention and process myths has been toxic to success in many organizations. The only option open to them for coping with the low success rates is “taking many shots on goal”. These myths are not reliable roads to innovation.

Sharpening the Definition

Having a clear definition of the outcome — adoption of new practice in a community — is essential to our goal of formulating the practices behind skillful, successful innovation. In the next four sections, we will sharpen our definition by digging deeper into these aspects:

- Community: the people who change their practices. How large are they? What do they value? What do they sacrifice to get the innovation?

- Practices: the ways of doing things. We will distinguish the practices being changed inside the community from the innovator’s practices that bring about the change.

- Adoption: the commitment to new practices and their incorporation into the prior practices of the community.

- Success: the goal of adoption is achieved. Three environmental factors support success — content expertise, social interaction, and moving into opportunities. How do we cope with failure? Learn and come back for later success? Abandon when the practice is obsolete or low value?

Community

The community is the set of people who adopt the new practice. In considering adoption, we will be interested in three aspects of the community: fit, size, and degree of change.

The first aspect, fit, concerns the alignment of the new practice with the already existing practices of the community. Everyone in the community shares a complex set of interacting practices as they carry out their lives and work. Innovation is about introducing a new practice into the mix. Often community members have to give up another practice to fit the new one in; the value of the new practice must exceed the cost of the sacrifice they must make to have it.

When Bob Metcalfe sold Ethernets, he had to show his clients how the Ethernet would enable their company to communicate and share information better than any of its current methods, and that it would open doors to new possibilities valuable to the company. He had to overcome their natural reluctance to change by showing them that the sacrifice was worth it.

In the early 1980s, Fernando Flores created The Coordinator, an email client that tracked progress in “conversations for action” — the conversations in which one person fulfills a request from another (Winograd 1986). Some organizations embraced the new email system enthusiastically, and reported several fold improvements in their productivity. Other organizations rejected it because they perceived commitment tracking as a form of surveillance. The Coordinator fit well with existing practices in the former type of organization, but the latter organizations perceived too great a sacrifice of their values.

The second aspect, size, concerns the number of people in the target community. Although the most popular innovation stories make it seem as if most innovations are very large, the truth is that the vast majority of innovations happen in small groups. There is considerable evidence that the size of innovations follows a “power law” — adopting communities of a given size are one-fourth as numerous as communities of twice the size. The big innovations catch our attention but the small ones are far more common.

In Chapter 2 we will tell the stores of innovators who produced innovations small (family of 7), medium (small-business community), and large (the world).

The third aspect, degree, concerns the amount of change required to fit the new practice in. A “sustaining innovation” is a small-degree change, usually involving an improvement in an existing practice to make it more productive (Christensen 1997). When Wilkinson Sword introduced the stainless steel blade, they did not change shaving, but made the experience less painful and less costly because the blades lasted longer.

In contrast, a “disruptive innovation” is a large-degree change, usually involving a change to the overall system that affects many practices besides the innovation, and often provokes resistance from those who do not want to change. Apple iTunes has been a disruptive innovation in music publishing because artists do not need a publishing house to offer their music in iTunes. Similarly, Amazon.com has been a disruptive influence in book publishing because anyone can self-publish.

Whether an innovation is considered sustaining or disruptive also depends on the time frame. Over a short period of time, Moore’s Law for computers (double the compute power for the same price every 1.5 years) can seem like a relatively modest change. But over a longer period, say 15 years, compute power increases by a thousand, which completely changes the way some things are done.

Practices, Performances, and Skills

We use the terms practice, performance, and skill frequently in this book. People interpret these common terms in different ways. Let us take a moment to define what they mean in this book.

Practices

The word “practice” appears prominently in our definition and in several related terms used throughout this book, including “the practice of innovation,” the “eight generative practices of innovators,” and “communities of practice.” The term “practice” has four senses:

- A customary way or pattern of behavior

- Exercise of a profession or discipline

- Developing a skill by repetition

- Name of a space of human interactions for taking care of concerns.

The first three are standard dictionary definitions and the fourth is more generic (Spinosa 1997).

When we speak of the members of a social community changing their practice, we invoke the first sense.

When we speak of the practice of innovation, we invoke the second sense.

When we speak of the eight generative practices of innovators, we invoke the second and third senses, meaning that all innovators exercise them and develop their performance through practice.

When we speak of communities of practice, we invoke the fourth sense. This sense can go quite deep and can evade our ability to describe everything involved in the practice. Consider the practice of telephony, which is concerned with people talking via telephone in order to communicate and coordinate with one another. How many people are involved in a phone call? At first glance you might think that only the two speakers are involved. But think again. All phone calls are routed through switching exchanges. Who maintains and repairs exchanges? Who repairs maintains and repairs intercity and intercontinental cables and microwave links? Who manages the people who do that? Who builds new exchanges and links? Who designs them? Who draws up the electrical diagrams and blueprints? Who programs the computers? Who does the research leading to the technology in the exchanges and links? Who provides operator and directory assistance? Who maintains account records? Who sends out the bills? Who processes the payments? Who sold the subscriptions to the parties who are talking? Who designs, builds, and sells the telephone instruments the talkers use?

If that is not enough, who designed and manufactured the silicon chips used in the switching computers? Who manufactured the fiber optic cables? Who manufactured the copper wires? Who set the standards for chips, cables, and wires? Who designed the protocols for using these technologies and links? Who brought about the international standards for the protocols? Who designed telephone instruments, jacks, plugs, connectors, and closet racks? Who designed the power supplies and backup units? Who provides normal electrical power? Who pays the bills for power and equipment? Who provided the predecessors of the current telephone technology? What concerns motivated them? How far back in time do we need to look to find all the people who contributions still matter today?

When you look this way, you see that hundreds of people are involved in a single phone call: the two who are talking and the hundreds of others who operate and maintain the telephone system. If you consider the historical sweep of time, you see that tens or hundreds of thousands were involved in the technology chains leading up to the current technology.

Suppose someone proposes downloadable ring tones for cell phones. What might it take for this to become a new practice? It will take people to design the data formats for the tones, place them on a server, modify the cell phone software to accommodate ring tone recordings, create and test new tones, build a marketing strategy for selling tones, integrate the billing of tone sales with other financial transactions, and provide enough additional bandwidth in the telephone equipment to accommodate people downloading tones. All these people must change what they do so that the ring tones become a new reality.

Once the downloadable ring tone practice is adopted, other parts of the space change. Many people will come to see tones as parts of their identities and as fashion statements. Many will combine the tones with caller-id, so that each incoming call rings a distinct tone identifying the caller. Many will want do-it-yourself kits that enable them to record and install their own ring tones at home. Many will want backup services so that when they buy a new phone all the caller-ids and tones can be transferred easily.

This is the nature of a community of practice. It goes deeper and deeper as you ask more questions about who is involved, what they do, and when they did it. There is no end. Everything is connected and interdependent. You cannot name most of the people who are or were involved, but you know they were there.

Now we see the true magnitude of the innovator’s challenge. Achieving a change of practice in a community means that many people have to go along, changing their individual practices together and integrating the new practices into ones that already existed. It means that the change has to produce enough value to motivate each person. It means that those who see insufficient value will resist. It means that the change must be consistent with historical concerns in the community.

In this book, our use of “practice” draws on all four senses described above. These statements capture what we mean:

Practices are recurrent actions that have outcomes.

Practices are performed by individuals or groups.

Practices are performed at different skill levels.

Practices cope with breakdowns.

Practices are embodied (they are not rule sets).

Practices include mental processes, emotional states, and body reactions.

Practices are embedded deeply in the context and history of communities.

This is why innovation is complex and there is no easy answer to the question, “what does the innovator do?”

Notice that the “eight practices of innovators” refer to what the innovator does and “change of practices in a community” to what the innovator accomplishes.

Performance

Innovation is a performing art. Its quality, impact, and extent depend on the performance skills of the innovator. We distinguish three levels of performance at innovating: novice, skillful, and masterful. Novice innovators act in accordance with their understanding of rules and steps of innovation processes. Skillful innovators act from their embodied skills in the key areas covered by the eight practices. Masterful innovators act from an embodiment so deep that their actions seem intuitive and unique as they mobilize entire communities to think, believe, and value differently. In addition, we tend to expect masterful innovators to be able to deal with large, complex, heterogeneous communities, and novice innovators relatively small, homogeneous communities.

A person can advance through these performance levels with practice and immersion in the communities to be changed. The novice can use this book as a guide to the rules of action in each of the eight practices. After a while, the novice becomes skillful, embodying the eight practices enough to do them well without much conscious thought. From our experience with our students, we believe that serious learners with help from good mentors or coaches can become skillful innovators within a year. After a much longer while, perhaps a decade, the skillful innovator becomes masterful, with substantial experience, deep embodiment, and a unique style and intuitive ability to effect change. The third part of this book explores the journey of mastery.

Skills

In addition to practices and performances, we refer frequently to skills in this book. It appears in phrases such as “skill at the eight practices” and “skill levels of innovators”.

A skill is an individual ability or capability to perform a practice acquired or trained by repetition. A skill is not the same as a practice — the practice is the context for the skill. There are numerous “communities of practice”, but no “communities of skill”.

The term “skill” often carries the connotation of capabilities that are relatively easily transferred from one domain to another. Transferability assumes that the new domain already hosts a practice in which the skill makes sense. Thus, one can learn the skill of debate in college and then put it to use later in the courtroom (as a lawyer), the boardroom (as an executive), or the Congress (as a legislator). One can modify a skill learned in one domain for another domain; a mechanic who specializes in Volvos can transfer to a shop that repairs Toyotas.

We will shortly introduce the eight practices of innovators. Since all domains host innovation, it is possible for an innovator to learn the skills of doing the eight practices in one domain and transfer them effectively to other domains.

While innovation is commonly accepted as a process, there is a long history of skepticism toward innovation as a skill. An important reason for the skepticism is that masterful innovators rely on much tacit knowledge for which no “training” regimen is known. Our contribution in this book is to reveal eight essential practices that are not heavily dependent on tacit knowledge. Learning them will greatly improve one’s success rate at innovation without requiring full mastery.

Adoption

When a community adopts a new practice they make three key commitments: considering it, adopting it for the first time, and sustaining it over a period of time. The first commitment is to discuss the new possibility; many proposed innovations died because their purveyors could not engage others in conversation about them. The second commitment is to an initial adoption, to try out the new practice, idea, product, or approach and see how it works. And the third commitment is to a continuing adoption, to take on the new practice, learn it, and integrate it into existing practices.

While working to elicit each of these commitments, the innovator will be challenged to demonstrate the value of the innovation. Each challenge entails costs, time, and energy. Each presents breakdowns and obstacles that an effective innovator must be able to deal with to prevent failure. Adoption is not the natural outcome of clever ideas or effective marketing; it is the result of innovators successfully demonstrating value and drawing people deeper into commitments to the new practice.

Success

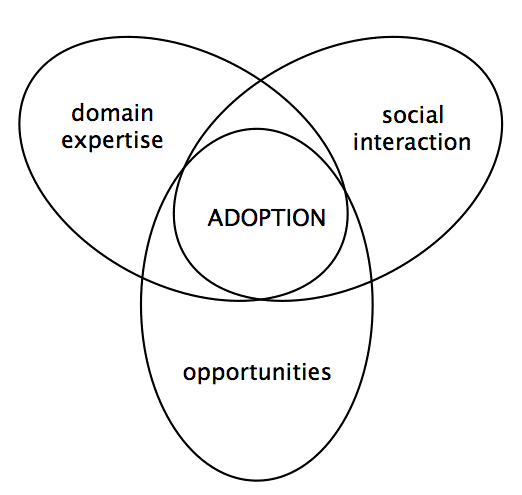

An innovator is most likely to be successful when three factors converge (Figure 2). The first factor, domain expertise, is your skill in the community of practice you aim to change. The greater your expertise, the more you know about deep concerns and subtleties, making you more likely to offer high value proposals that fit your community. Gladwell (2008) reports studies showing that the greatest chances of success occur for people who have achieved mastery by putting in at least 10,000 hours of practice. He is not saying that anyone who accumulates 10,000 hours of practice will be a master, but rather than mastery takes a long time: 10,000 hours is 10 years at 3 hours practice a day, or 3 years at 9 hours practice a day. We focus in this book on the path to mastery, but not on how to gain experience in your field.

Figure 2. Success at innovation lies at the interaction between the innovator’s domain expertise, social interaction skills, and ability to recognize and move into opportunities (realizable possibilities).

The second factor, social interaction practices, is your skill at influencing others. John Seely Brown, quoted at the start of this chapter, says that the point of the innovation practices is to mobilize action around the idea. Mobilizing other people around your ideas requires certain social interaction skills. Gladwell (2008) illustrates with examples of people of high expertise but low social interaction skills, who were ultimately unsuccessful. The eight innovation practices at the core of this book are all essential social interaction practices whose outcomes are all necessary for innovation.

The third factor, opportunities, acknowledges that you cannot control your environment but you can control how you engage with it. Successful innovators have a high sensitivity to people’s concerns and breakdowns, an ability that might be called “reading the world”. Once they sense opportunities, they are good at moving toward them by making offers to the members of the community. The story of Pasteur (prolog), who discovered germs and developed the first vaccines, illustrates a man with extreme sensitivity and an ability to tell when something is about to become important. He engaged with flair and drama to catch people’s attention when they were the most ripe for change — in the middle of a big breakdown.

The eight practices of this book — discussed next — foster your ability to sense opportunities in the world and effectively mobilize change. There is no reason to be stuck at the 4% success rate. You can go much higher.

Overview of the Eight Practices

In Disclosing New Worlds (1997), Charles Spinosa, Fernando Flores, and Hubert Dreyfus analyzed innovations in business, social, and political domains. They identified a common pattern that the entrepreneur, social activist, and virtuous citizen engage in. They called the pattern “history making” because in each case the person intervened in the practices of a community and changed its course of history. Here is our summary of their pattern.

The Prime Innovation Pattern

| They find in their lives and work something disharmonious that common sense overlooks or denies.They hold on to the disharmony, allowing it to bother them; they engage with it as a puzzle.Eventually they discover how the commonsense way of acting leads to the disharmonious conflict or failure.They design or discover a new practice that would resolve the disharmony. The new practice comes from one of three sources:It is already a background practice of the community, but has been dispersed and nearly forgotten. Recovering it is called articulation.It is a marginal practice on the fringes of the community’s awareness, usually resulting from an invention. Bringing it to the center is called reconfiguration.It is a standard practice of another community, which can be mapped and adapted into the current community. Importing it is called cross-appropriation.They make a deep commitment to getting the new practice adopted in their community. |

When we studied innovation stories and interviewed serial innovators and volunteers in collaboration networks, we were struck by the universality of this pattern. It gave us a way to look beyond their personalities, virtues, and vices, and examine the types of commitments they made and fulfilled. We discovered that each commitment was directed at one of the outcomes listed in the chart below. We named the eight practices after these outcomes.

The Outcomes of the Innovation Practices

| Sensing: Bringing forth the new possibility that would bring value to the community.Envisioning: Building a compelling story of how the world would be better if the possibility were made real.Offering: Presenting a proposed practice to the (leaders of the) community, who commit to consider it.Adopting: Community members commit to trying out the new practice for the first time.Sustaining: Community members commit to staying with the practice for its useful life.Executing: Carrying out action plans that produce and sustain adoption.Leading: Proactively working to produce the outcomes of the previous six practices, and overcoming the struggles encountered along the way.Embodying: Achieving a level of skill at each practice that makes it automatic, habitual, and effective even in chaotic situations. |

We also discovered that each practice has a somatic aspect as well as its conversational aspect. The somatic aspect accounts for body reactions and emotions that accompany language. The somatic aspect takes a role front and center in the eighth practice (embodying).

The structure of the eight practices is summarized in the chart below. The first two are the main work of invention and the next three the main work of adoption. These five tend to be done sequentially. Each of the final three creates an environment for effective conduct of all the other practices. Although executing, leading, and embodying are fundamental to many domains of practice, are special for innovation: we have to execute the innovation commitments, be proactive in promoting the innovation, and be sensitive to how other people listen and react.

Structure of the Innovation Practices

| The main work of invention | 1 | Sensing |

| 2 | Envisioning | |

| The main work of adoption | 3 | Offering |

| 4 | Adopting | |

| 5 | Sustaining | |

| The environment for the other practices | 6 | Executing |

| 7 | Leading | |

| 8 | Embodying |

In reality, these practices are not sequential at all. The innovator moves constantly among them, refining the results of earlier ones after seeing their consequences later. It is better to think of them as being done in parallel rather than in numerical order.

These eight practices are special in that their structures are completely observable in both their conversational and somatic aspects. This fact enabled us to specify how to teach, train, and coach the practices. The overall effectiveness of these practices depends on the innovator integrating them into a single, coherent style. The practices affirmatively answer the question, “Is innovation a learnable practice?” They define what it means to be a skillful innovator.

The specification of each practice has two parts. The anatomy describes the structure of the practice when it goes well and produces its outcome. The characteristic breakdowns are the most common obstacles that arise in trying to complete the practice. Within the practice, the innovator steers toward the desired outcome and copes with breakdowns that may arise. We specify each practice this way in its own chapter in Part 2 of this book. A summary of the specifications is included as Appendix 1 of this book.

In Appendix 2 we have included a self-assessment tool to help you evaluate your level of skill at each of the practices, and your overall level of coherence among the practices.

After much study of successful and unsuccessful innovations, we demonstrated these features of the eight practices:

- They are fundamentally conversations. Each practice is manifested as a conversation that the innovator engages with and moves toward completion.

- They are universal. Every innovator, and every innovative organization, engages in all of them in some way.

- They are essential. If any practice fails to produce its outcome, the entire process of innovation will fail.

- They are embodied. They manifest in bodily habits that require no thought or reflection to perform. Thought is directed to strategic issues, not to the performance of the practices.

We will discuss and ground all these claims in the remainder of the book.

Embodiment

To his observers, World Wide Web innovator Tim Berners-Lee has an uncanny ability of zeroing in on the right conversations, connecting with his audience, and addressing concerns. He maintains a strong focus even when surrounded by chaos. He is able to forge consensus in the midst of seemingly intractable disagreement. His ability is actually a high level of embodiment of the eight practices. We know this because we have analyzed the conversations he engaged in during the formation of the Web (Berners-Lee 2000). He demonstrates the power of embodied, habitual skill in conversations and interactions with others.

A practice is embodied when its performance is transparent, automatic, and habitual. You can put an embodied skill to action immediately without thinking about it. In working with our students, we discovered that teaching the basic practices purely as conversational patterns was not enough to achieve the embodiment for coping with breakdowns. Even though they had strong command of the linguistic patterns, many students still had difficulties inspiring trust, connecting with their audiences, listening for deep concerns, and responding well in chaotic situations. They tended to react defensively to breakdowns. When defensive, they wound up focusing mainly on themselves, not on the listening of others.

This is why we identified the eighth practice, embodying. It is concerned with the question, “How did the innovator integrate language, emotion, and body to enable the other seven practices to become automatic, habitual, and effective?” This more-advanced practice is founded in somatics, a discipline that deals with the integration of mind and body. It is the key to reaching the higher levels of performance in the other practices.

The eighth practice develops the capacity to listen well, connect, accept, show compassion, and produce a receptive listening in the community. It helps read another’s presence and energy, modify one’s own presence, sense how others experience their surroundings, blend with others in moving them toward adoption, and retrain one’s own habitual (conditioned) tendencies.

Conclusion

Our main objective in this book is to help you develop a sensibility to how innovation is generated and to show you how to attain the skillful levels through practice. Even if you use the book only to be aware of the practices, simply having this sensibility is an important step toward being skillful at it. You will become aware of new aspects of familiar situations and pay attention to them differently. We also want to reveal some of the more advanced practices of masters even though we cannot formulate definitive ways of learning them.

The path to innovation is both challenging and rewarding. The innovation process is full of complexities; we cannot remove the complexities, but we can provide you with a map to success, guidance on where to put your attention, and practices for developing the skill. You do not need to master everything in the eight practices to see results. As you become more proficient at each practice, you will find yourself getting better and better at innovating.

This book will help you shift your interpretation of innovation from a high-risk mysterious process to a skill set at eight universal practices that can be learned and trained. From our experience with students, we believe that those practices will enable you to increase your success rate at innovation, often significantly. And they are the launch point of a journey to innovation mastery.

Bibliography

Barabasi, Albert-Laszlo. Linked. Plume (2003).

Berners-Lee, Tim. Weaving the Web. Harper Business (2000).

Bush, Vanevar. Science: The Endless Frontier. Available as an historical document from the National Science Foundation; www.nsf.gov/about/history/vbush1945.htm (1945).

Christensen, Clayton. The Innovator’s Dilemma. Harvard Business (1997).

Colvin, Geoff. Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else. Portfolio: Penguin Group (2008).

Denning, Peter J. “The social life of innovation.” ACM Communications 47, 4 (April 2004), 15-19.

Denning, Peter J., and Robert Dunham. Innovation as Language Action. ACM Communications 49, 5 (May 2006), 47-52.

Dreyfus, Hubert. What Computers Still Can’t Do. MIT Press (1972, 1992).

Drucker, Peter. Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Harper Business (1993). (First published by Harper Perennial in 1985.)

Dunham, Robert. Self-Generated Competitive Innovation with the Language-Action Approach. The Center for the Quality of Management Journal 6, 2 (Fall 1997).

Evans, Harold. They Made America: Two Centuries of Innovators from the Steam Engine to the Search Engine. Little Brown (2004).

Gladwell, Malcolm. Outliers: The Story of Success. Little Brown (2008).

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. Innovation: The Classic Traps. Harvard Business Review 84, 11 (Nov 2006), 72-83.

Kline, Stephen J., and Nathan Rosenberg. An overview of innovation. In The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth. National Academy Press (1986), 275-305.

Metcalfe, Robert. Invention is a flower; innovation is a weed. MIT Technology Review (November 1999). Available: www.technologyreview.com/web/11994/?a=f

Searle, John. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press (1969).

Searle, John. Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge University Press (1985).

Spinosa, Charles, Hubert Dreyfus, and Fernando Flores. Disclosing New Worlds. MIT Press (1997).

Tuomi, Ilkka. Networks of Innovation. Oxford Press (2003).

Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Kahn and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press (2004).

Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America. Touchstone of Simon and Schuster (1992).

Weatherford, Jack. Genghis Kahn and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press (2004).

Wills, Garry. Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America. Touchstone of Simon and Schuster (1992).

Winograd, Terry and Fernando Flores. Understanding Computers and Cognition. Addison-Wesley (1986).

Yager, Tom. Innovate, or Take a Walk. InfoWorld (April 29, 2004), 69.

© 2004-2009, Peter J. Denning and Robert Dunham. Permission needed to reproduce in any form.